The complexity of the war in eastern Congo with its entangled web of actors pursuing a multiplicity of agendas can be overwhelming and confusing. Once known as “Africa’s World War”, the conflict in the Congo once embroiled nine countries and a myriad of local and foreign rebel groups. Over the years, relationships have shifted. Friends have become foes, foes have become friends, and political circumstances have changed, frequently altering the power equation in Africa’s Great Lakes Region.

Because the Congolese state does not have a monopoly over the means of violence in eastern Congo, and elements of its armed forces often engage in abuses similar to those of militias, the region is a fertile environment for the development and growth of armed groups and warlordism. As a result, violence is frequently traded for money, political power, and control of natural resources. This situation has left Congo’s North and South Kivu provinces in a protracted crisis.

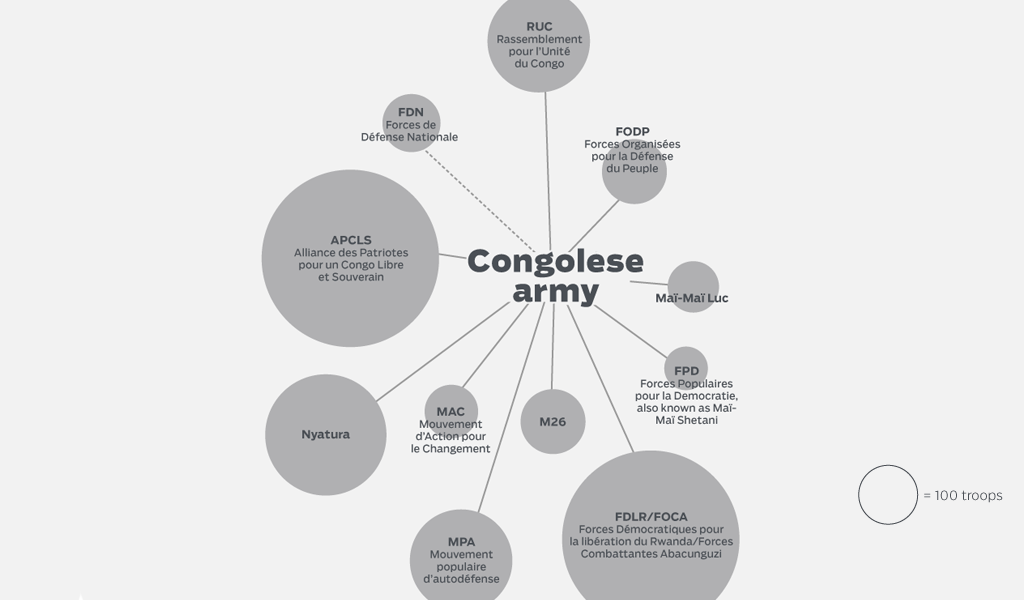

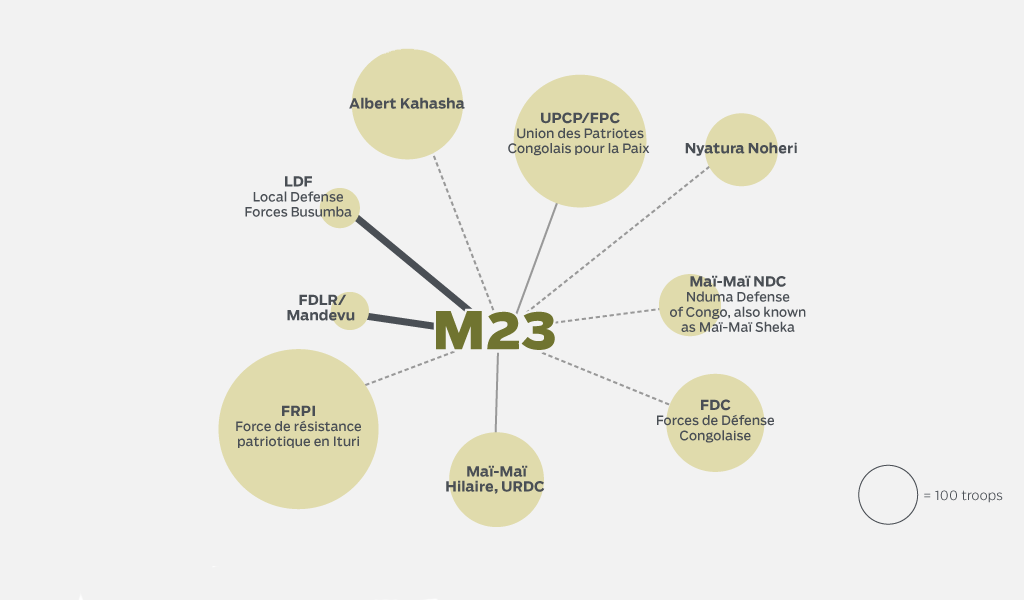

One of the latest outgrowths of the insecurity is the M23 rebel group, which defected from and is now fighting against the Congolese national army. Each of these parties pursues its interests through a set of relationships with other armed groups.

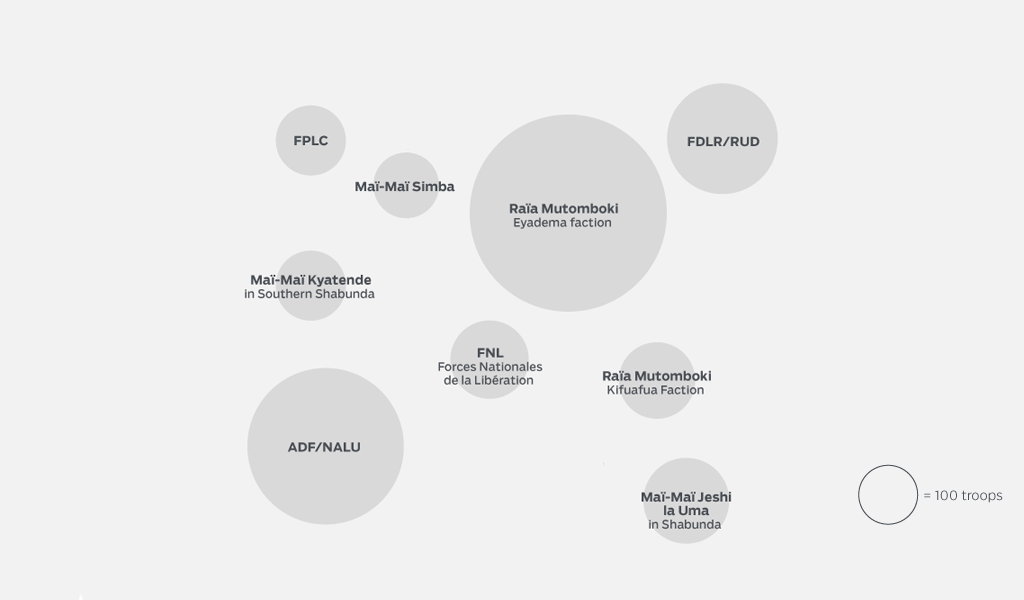

The infographic sets out the strength and nature of the relationship between the Congolese army, or FARDC (Armed Forces of the Democratic Republic of Congo) and its allies, and the M23 rebels and their allies.